THE PRIMEUR SEASON HAS RETURNED. With it comes the comedy of ratings by thousands of professionals or self-proclaimed experts. In a great vintage, this means a proliferation of stratospheric scores. Of course, instead of thanking the heavens and their own talent for the good marks they have received, which will enable them to sell at a higher price, the producers are quick to pay tribute to the generous note-givers on their social networks. At the same time, we are seeing the emergence of a new ethic of wine tasting, one that distrusts knowledge in favour of a subjective judgement that would be more independent of trading and therefore more ethical. This is the exact opposite of what we try to practise at Bettane+Desseauve. Expertise is not something one can auto-proclaim, even with national diplomas or the myth of the press card. It has to be earned if it is to be respected. It requires a long apprenticeship and practice. You can’t judge a producer’s individual success in a given vintage on the basis of pleasure alone. Even less so when you have the privilege of ranking it by an arithmetical rating. And even less so when you would have a public that likes to be gullible believe that this score has an absolute value.

Forty years of judging the quality of wines. As many years of assigning a value that can change everything. The tool seems quite inadequate to reflect the vintage that has just been born. Change is just around the corner.

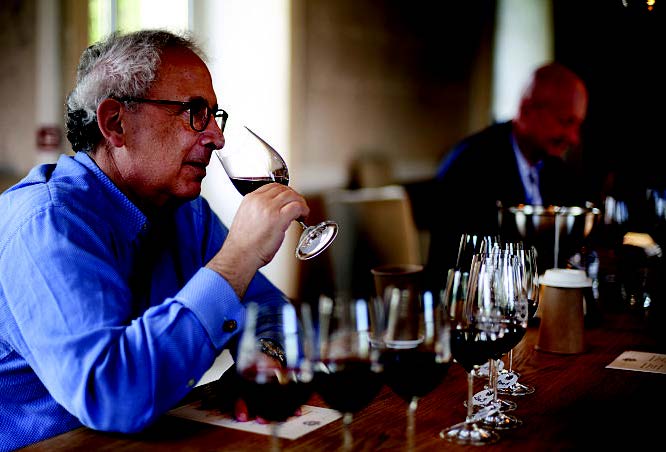

On the contrary, we must insist on its relative value, specific to the vintage and the particular conditions of the tasting: the order of the wines and the individuality of the terroir, the grape varieties, the working methods, the temperature, the atmospheric pressure, the shape of the glass, the vagaries of samples taken during maturation, an environment more or less conducive to the taster’s concentration and, above all, the speed with which the judgement is made. How often is it that three centilitres at the bottom of a glass, judged in less than three minutes, are claimed by the producer happy with his score as a definitive reference! We owe it to ourselves to give as much space as possible to objective factors. Having attended the harvest, followed the vegetative cycle, eaten the grapes to judge their potential, tasted the first musts, knowing the potential of the terroir, the oenological balances specific to any fine wine, taking into account the choices and practices of each producer and, from these elements, which is even more delicate and subject to discussion, prejudging the future of what is still an embryo and a living being obeying the laws of nature. A good method of prioritising wines is, at least once, blind tasting. It forces us to concentrate solely on the personality of the product, without reference to the label, and then to compare it with everything we know about the cru, the producer, the vintage and our agronomic and oenological ideals. Blind tasting is becoming increasingly rare. And increasingly forbidden by producers’ associations. The most famous crus are naturally too afraid not to receive the blind tasting score that justifies their selling price and reputation. It is human and understandable. Every winegrower likes us to taste in his presence and with the information he gives us. It is impossible to visit all the crus, even in a month of long daily tastings, and above all to take into account the inevitable variations in tasting conditions at each estate from one day to the next. Everyone should try the following experiment, which I was lucky enough to experience. Have the producer take a representative sample from a double magnum at 9 o’clock in the morning. Ask him to decant it into half-bottles. Taste each half-bottle, whether it comes from the top or the bottom of the double magnum, at 4pm, in an individual glass, to which you add a glass from another sample taken directly from the half-bottle, in random order. Then ask yourself if it’s the same wine and if you would give each glass the same arithmetical rating. Another disturbing and (avoidable) way of working, if you want to give a fair idea of the hierarchy of successes, is to give these ratins on the spur of the moment and send them so quickly as to be published before the others, before having tasted all the wines not only from the same appellation, but also from the same region, and several times if possible. How can we justify a mechanical commentary on the flavour and construction of the wine, as we too often read, on the basis of these few centilitres and these few minutes? Development in the glass for half an hour or more is crucial in such young wines, just as a comment on the integration of oak before the additional year of ageing is ridiculous. At Bettane+Desseauve, we prefer to take our time, compare blind and with label, and discuss our individual feelings within our small team. And above all, we rank our ratings clearly and only at the end of our investigation. On a scale that would ideally be twenty points (from 80 to 100) for the wines we like, and which we often reluctantly reduce to ten points, because of the incomprehension of many producers used to 90/100 scores from international critics. Let’s not forget that, within the same appellation and with the same quality in the crus that work well, the price of a wine can vary from 1 to 20, or more. We strongly assert the relative nature of our hierarchy, even if the average of the scores does reflect the success of the vintage in absolute terms.

🔓 this article is free access for all.